Defining low-carbon hydrogen: How to do it right

The European Commission is about to set new rules on how to calculate greenhouse gas emissions from hydrogen production, defining what can be classified as ‘low-carbon’. What methods and definitions are the most accurate, and how can they be integrated into EU law? Find out in our blog.

Not all hydrogen is created equal. It can be produced in many different ways — sometimes with high emissions, sometimes nearly emissions-free. Definitions and methods to calculate greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions from hydrogen need to be accurate and ambitious to avoid greenwashing and support the EU in meeting its 2030 and 2050 climate targets.

Setting definitions for assessing GHG emissions from fossil fuel-based hydrogen production is the role of the Low-Carbon Fuels Delegated Act, which the European Commission is supposed to adopt before 5 August.

The big question: what kinds of hydrogen will qualify as ‘low-carbon’?

New measures will create political legitimacy around the notion of low-carbon hydrogen. This raises the stakes for producers because hydrogen that qualifies as such could unlock access to state aid subsidies and other market incentives. Producers have a vested interest in pushing for more flexible criteria to ensure their projects can benefit.

The EU’s environmental credibility is also at stake. A weak definition could misdirect investments away from renewable hydrogen and make it less competitive, delaying decarbonisation by encouraging solutions that are neither fully clean nor guaranteed to be phased out.

How can policymakers ensure that the low-carbon definition is accurate and ambitious?

The risks of a weak definition

From steam methane reforming, electrolysis, methane pyrolysis, and gasification, there are many ways to make hydrogen, and many variations in how much greenhouse gases are emitted in the process.

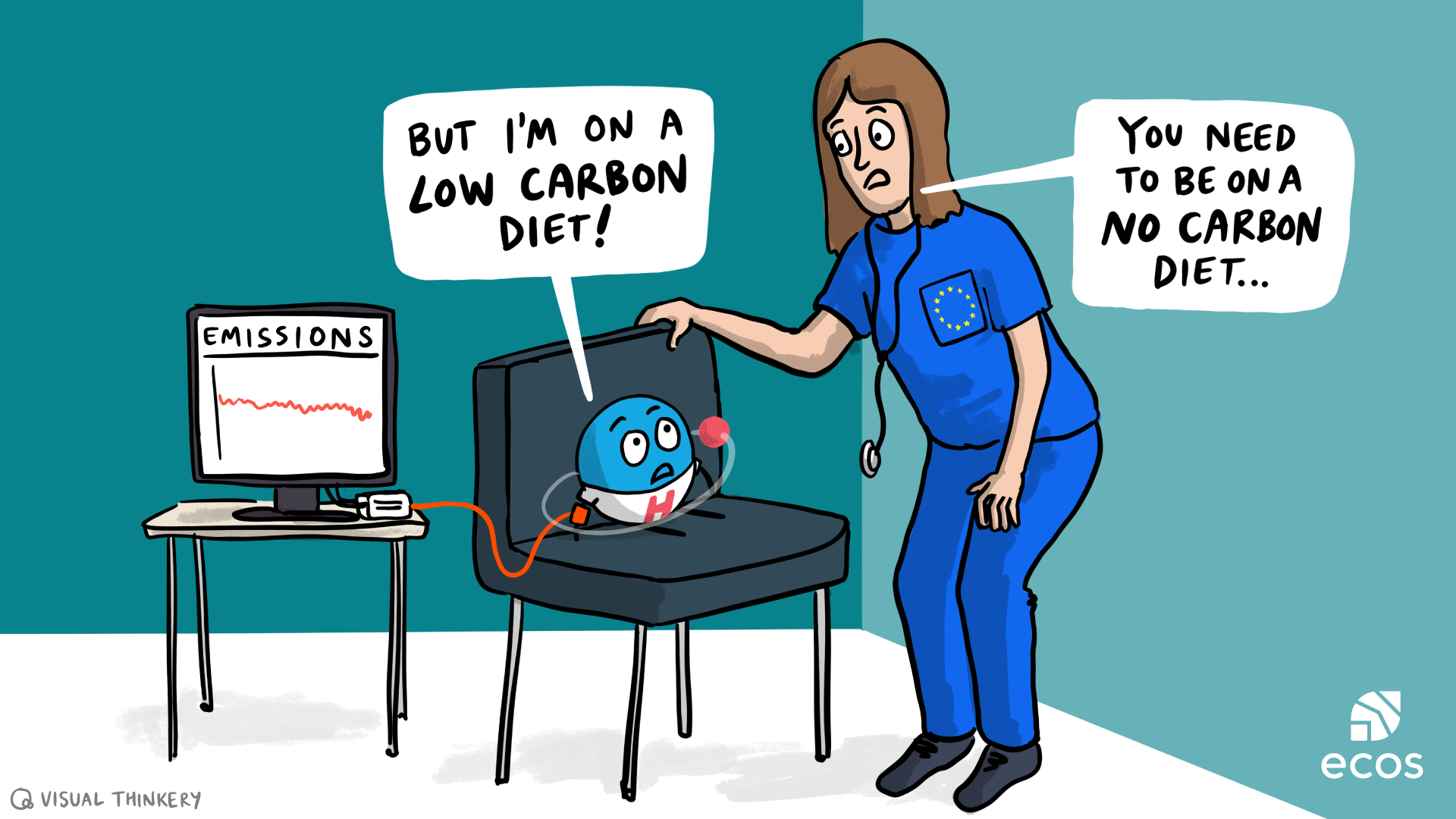

The European Commission is considering a definition of low-carbon that includes hydrogen created using fossil fuels and carbon capture and storage (CCS). However, even the best CCS systems let tonnes of CO₂ emissions escape — and they also carry the burden of upstream methane leakage. So, any form of ‘low-carbon’ hydrogen will still emit a large amount of greenhouse gases. Low-carbon does not mean no carbon.

Classifying such hydrogen as low-carbon, with all the market benefits that would bring, risks unfairly distorting the level playing field for renewable hydrogen — the kind with near-zero emissions, produced using only renewable electricity. It would also hide vast differences in emissions performance between projects, making them all appear to be equally climate-friendly, despite variations in how much emissions are reduced.

Without strict criteria to mitigate these risks, labelling fossil-fuel based hydrogen with high emissions as low-carbon would mask fossil fuel dependence, lock-in fossil-fuel infrastructure, and waste public money. Resources should be clearly directed towards renewable hydrogen — as defined in existing rules — instead of dirtier options that are supposed to be transitional but carry no guarantees.

Methane: A potential loophole

The latest draft of the Low-Carbon Fuels Delegated Act miscalculates the true climate impact of fossil-based hydrogen because, even after being increased since the first draft, it still underestimates by more than half the global warming potential of methane, as well as its leakage potential. This must be improved in the final text, otherwise some high-emission fossil hydrogen will be granted low-carbon status, polluting with impunity and locking Europe into continued fossil fuel dependence.

Methane is a potent greenhouse gas, with a much higher global warming potential than CO₂ in the short term — it is as much as 84 times more potent than CO₂ on a 20-year timescale. Leakage occurs across the entire fossil gas supply chain — from extraction and processing to transport and distribution. It also varies widely, from 0.2% in tightly regulated countries like Norway to over 5% in regions with poor monitoring and infrastructure, such as parts of North Africa or Central Asia. Leakage emissions are consistently underestimated and poorly monitored, so ensuring values that reflect different realities on the ground is crucial.

Building an ambitious definition

With the impacts of climate change evident, and heatwaves engulfing Europe as we write, the need for environmentally sound legislation is ever more dire. An ambitious definition of low-carbon hydrogen would contain:

- Correct methane global warming potential and leakage values. Values that are too low risk institutionalising under-reporting and enabling greenwashing. Read the details in our consultation feedback on the Low-Carbon Fuels Delegated Act and joint NGO letter calling for more ambition on methane.

- An end to the greenwashing of fossil-based hydrogen. Fossil-based hydrogen should only be labelled as ‘low-carbon’ when it can demonstrate that it meets the strictest climate criteria. This would stop renewable hydrogen from being disadvantaged in a non-level playing field.

Hydrogen is no silver bullet

If produced with renewables, hydrogen has a role to play in the energy transition, but it is no silver bullet, and its uptake should not be artificially boosted just to create short term gains for hydrogen producers.

If produced with renewables, hydrogen has a role to play in the energy transition, but it is no silver bullet, and its uptake should not be artificially boosted just to create short term gains for hydrogen producers.

Introducing the wrong criteria now will only compromise the effectiveness of climate and energy laws, leading to much bigger problems in the long-term.

Want to know more? Read this blog about the importance of calculating hydrogen emissions correctly.

By

By  By

By