Message on a bottle: new rules that will make or break EU recycling goals

Regulators are coming for single-use plastics. In the EU, PET bottles will need to include at least 25% recycled plastic by 2025. The bar will be raised to 65% and extended to all single-use plastic beverage bottles by 2040 if new draft packaging rules are passed. But how to count the amount of recycled plastic in a bottle? If rules are too loose, this could become a meaningless accounting exercise – and the first step towards greenwashing. The EU is expected to set those technical rules in the first quarter of 2023. Out of the limelight, this is a watershed moment for the end of unjustified green claims about recycled plastic. What to expect?

Many plastic bottles claim to be made from 50%, 70% or even 100% recycled plastic. We can only expect to see more of these labels in the future. Manufacturers are preparing to comply with the EU’s Single-Use Plastics Directive’s (SUPD) minimum requirements for recycled content, entering into force as of 2025.

Unfortunately, defining how much recycled plastic a bottle contains is much more complicated than it seems. Depending on the method used, the declared percentages might have very little to do with reality. Without strict rules for calculating recycled content, EU efforts to promote the market uptake of recycled plastic could be a mere waste of time.

This winter, the EU is setting rules for plastic content accounting

In July 2021, the SUPD entered into force, tackling ten of the most common single-use plastic products. First in the infamous top ten, drinks bottles.

Most beverage bottles are recyclable, even if the amount of plastic ending up in landfills could lead us to think otherwise. The SUPD requires every EU country to ensure that PET beverage bottles incorporate at least 25% recycled plastic by 2025.

The European Comission has now upped the ante. In November 2022, it proposed a new regulation establishing that single-use beverage bottles must be made out of 30% recycled plastic by 2030. The bar should be raised to 65% as of 2040. These rules, which are part of the new Packaging and Packaging Waste Regulation, are still up for discussion at the European Parliament and among member state governments.

While counting recycled content may sound simple, depending on how you calculate those figures, they could mean very different things for the bottle in your hand. Details on how to crunch the numbers are not yet defined. The Commission is now setting the rules of the game for declaring these figures in a so-called ‘implementing decision’ of the SUPD.

Different approaches to plastic content accounting

When a product’s label indicates the amount of a certain material inside, it is often not an accurate reflection. Due to the scale of the manufacturing process, the mix of materials, and the drive towards greater efficiency, figures are only estimates. But with a growing awareness of health, environmental and safety concerns, there has been a push to better trace the contents of individual products – and to prevent misleading marketing claims.

This comes down to chain-of-custody models. Put simply, these are the systems for documenting the use of a certified material through the supply chain. In other words, if you buy a fizzy drink in a bottle claiming to be made from 50% recycled plastic, it will have been through a chain-of-custody model to ensure this share of recycled material was actually employed at some point in the process.

Three chain-of-custody models for measuring plastic content

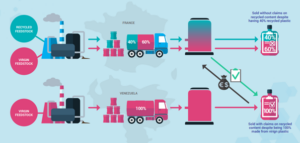

There are three main chain-of-custody models that the European Commission can choose from when setting EU-wide accounting rules. Two of those models can help ensure high traceability of recycled plastic by coupling the material with its actual recycled content. They are the ‘segregation’ model, and the ‘controlled blending’ model (also known as the mass balance approach ‘at batch level’).

The third option is applying mass balance at the level of a site (e.g. a recycling plant) or several sites. This model usually opens the door to massive greenwashing as it gives manufacturers too much freedom to allocate recycled plastic content to products of their convenience.

Let’s dive into each of these models to learn more.

1. Segregation – the ideal model for honest claims

Segregation is the simplest, most straightforward model. It ensures that what you buy is what you get. As the name suggests, this model keeps recycled plastic and virgin plastic separate at each stage of the supply chain. This is the only system that allows to honestly claim that a plastic bottle is made out of 100% recycled content. Strict segregation is not always possible or affordable, but it should be a privileged option in the Commission’s approach.

2. Controlled blending or mass balance at batch level with proportional attribution – the next best thing

Another model is ‘controlled blending’, applying the mass-balance model at the batch level (as defined in ISO standard 22095:2020). Using this system, recycled and virgin plastic would still be mixed – but according to strict supply chain traceability and proportional attribution criteria. As a result, we would have a good knowledge of what share of recycled plastic the final product contains.

Also, the model relies on the proportional attribution of the recycled output, improving the quality of the claims made. As a basic principle, if you use 40% recycled plastic and 60% virgin plastic to make your bottles, you can claim that a maximum of 40% of the total product produced is made from recycled plastic.

It is a relatively simple system, able to give a reliable and consistent estimate of the recycled plastic share in a finished product. It is a model that the Commission’s implementing decision should consider as second best. Applying this model would consistently drive demand for recycled inputs, mainstream investments into facilities able to process secondary raw materials, and give an honest picture of the environmental characteristics of a product.

3. Mass balance with free attribution – a model which could lead to massive greenwashing

Unfortunately, the mass balance traceability system becomes much less accurate when using chain-of-custody models allowing for the allocation of recycled content without reflecting the reality. This is the case, for example, when the system accepts that a facility which uses 1 tonne of recycled plastics issues a certificate so that this amount is claimed by another facility, which has not used any recycled materials. This can be done between multiple production sites, countries, or even continents. This model even allows aggregating plastics from factories producing different types of products made of polymers ranging from textiles to packaging.

If manufacturers are allowed to freely attribute the percentage of recycled content to products of their choice, there is a risk of massive greenwashing – and this is why the EU should not even consider this option.

Let’s say a company uses 40% of recycled plastic in its factories. The company produces 50% polyester for the textiles sector, and 50% PET for the packaging sector. With such flexible methods, the company could label 80% of the bottles ‘made from 100% recycled plastic’ and leave the rest without a label. They could then sell these ‘recycled’ bottles where they felt the claim might be the most attractive to consumers, even though it does not accurately reflect reality.

Where free attribution is used, a lot of valuable information is lost. For instance, we don’t know how much virgin plastic was used in the process altogether. With free attribution, no one knows what makes up a bottle – not manufacturers, consumers, or waste managers.

Worse still, when fully decoupling from real physical recycled material, manufacturers can simply ‘cook the books’. They can shift around the percentages to technically comply with the 25% and 30% requirements without actually doing much to increase their use of recycled material. They can also shift the percentages to the only sectors where minimum recycled content targets exist, such as the packaging sector, and not to clothes, as there is no target for the textile sector.

Segregation and controlled blending – the only two models that are fit for purpose

The Commission’s implementing decision is the make-or-break moment for the new minimum requirements on recycled content in plastic bottles. It must clearly point to segregation and controlled blending as acceptable chain-of-custody models for plastic bottles. This will mean that manufacturers will genuinely need to increase their use of recycled content while making honest claims about their products.

If, however, mass balance with free attribution becomes a viable option, the Single-Use Plastics Directive targets, and the new goals set in the Packaging and Packaging Waste Regulation, could become a meaningless accounting exercise.

If a bottle is labelled as made from 80% recycled plastic, that should really be the case. Only then will we know that companies are truly stepping up for the planet – and that consumers are not misled. We need a clear message on a bottle – one that reflects reality, not a smokescreen.

By

By