Building a European Affordable Housing Plan with what we have

Europe is facing a double challenge: reaching energy, climate, and circularity goals while also ensuring affordable, accessible, and healthy housing. Too often, these two challenges are put against one another. However, for a built environment that works for people and nature, the upcoming European Affordable Housing Plan (EAHP) should take advantage of how environmental and social aspects can work together. With fellow experts from Natuur & Milieu and Lund University, we look at how tackling inefficient use of empty or underused buildings can ensure affordable housing and reduce environmental impacts.

Access to housing is a right – clearly affirmed in the UN’s Universal Declaration of Human Rights, the EU’s Charter of Fundamental Rights and the Pillars of Social Rights. Yet, housing across Europe has become unaffordable to many. Eurostat data shows that housing costs in Europe have increased by an average of 48% between 2015 to 2023.

The knee-jerk reaction to this could be to ‘build, baby, build’ – but the predominant way of building cities is heavily unsustainable. Construction works rely on highly emissive materials – steel and cement alone make up 9% of the EU’s yearly CO2 emissions.

Squaring the environmental and social aspects of building projects is a delicate but necessary exercise. Recognising how these aspects can reinforce one another and where trade-offs exist is a crucial starting point.

Let’s do better than ‘build, baby, build’

Future constructions – when aligned with European legislation aimed at making new builds more sustainable, such as the Construction Products Regulation and the Energy Performance of Buildings Directive – have a role to play. But what if the EU were to make use of empty and underused buildings, including the 1/5 of EU conventional dwelling registered as unoccupied, to increase supply in a cost-efficient way while also reducing environmental impacts?

The Dutch experience: most buildings are already there

In the Netherlands, the housing shortage is among the most urgent societal issues. Despite an annual target of 100,000 new homes, construction lags and the shortfall is projected to exceed 400,000 in 2025. At the same time – and as a result – housing prices continue to rise, placing affordable housing further out of reach for many citizens.

Yet, the Netherlands has over 8 million existing homes, built mostly for families of four, while the average household size has shrunk to just two. Single-person households have more than tripled in the past 75 years, leaving a growing mismatch between housing supply and demographic reality.

This underuse of space presents a major opportunity. Natuur & Milieu commissioned work to EIB (Economisch Instituut voor de Bouw) to investigate this untapped potential and found that by splitting, building additional living floors on top, or converting existing buildings for residential use, the Netherlands can deliver between 100,000 and 120,000 additional homes by 2030. With subsidies and more lenient municipal regulations, this potential could increase by another 25,000 to 37,000 homes.

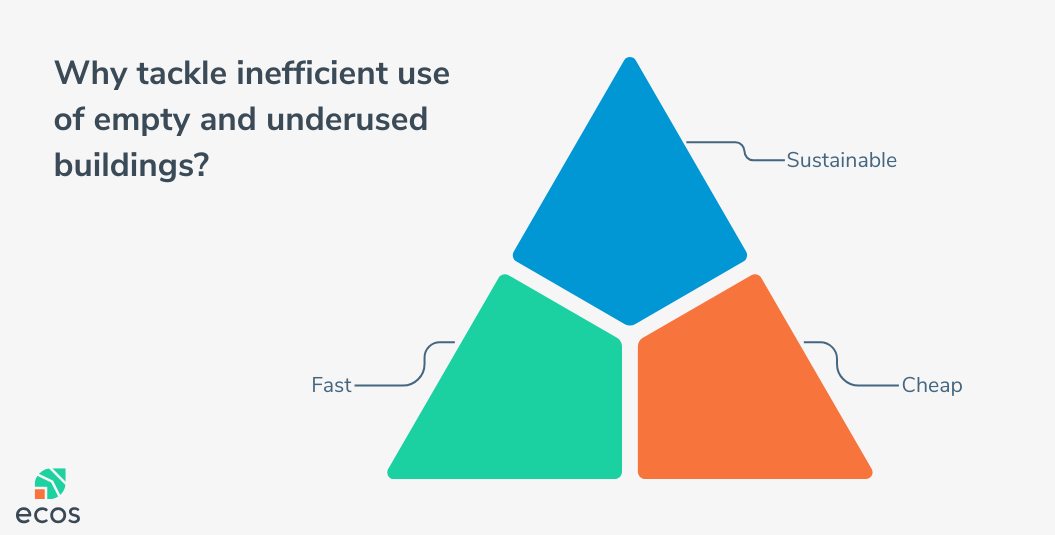

Better use of the existing stock not only alleviates the housing crisis: construction times are shorter, (labour) costs can be lower, nitrogen emissions are lower, and scarce land is preserved. Carbon emissions savings are also considerably lower with splitting, transforming homes, or building on top, saving respectively 85%, 66%, and 50% of emissions compared to average new builds.

Dutch national and local governments are starting to recognise the potential of better using the existing housing stock as it was confirmed at the 2024 Woontop – the Dutch national housing summit. However, various local rules and financial barriers still stand in the way.

How can policies and standards clear the way?

The building industry is heavily regulated to ensure a safe work and living environment. However, these regulations and standards usually govern new constructions and the use of new materials. Standards in the built environment help in calculating energy and social performance of buildings, as well as life-cycle assessment, quantifying impacts that operators must limit. To streamline the reuse of current buildings, constructions, and materials for future housing development, new standards need to be developed accordingly. For this, a new regulatory framework first needs to be set – and the European Affordable Housing Plan is the perfect opportunity to kick this work off.

To be a success, the plan must:

- Reinforce housing as a right – and a part of the built environment. A built environment that works for people and nature is instrumental to deliver affordable and sustainable housing projects.

- Make the best of the building stock already available by supporting and coordinating effective renovation and repurposing plans across Member States.

- Unlock the full potential of standards. Standards mainstream methodologies to improve the way we build, assess, and repurpose buildings. The EAHP should leverage them to make reuse of the current building stock easier – and address Europe’s housing crisis.

- Add inventories as a starting point. Inventories should cover the condition of existing constructions, including their remaining service life, need for reinforcement, and potential for added space. This practice must be streamlined: a standard for inventories must also include a comprehensive investigation of built-in materials and components, while allowing practitioners to understand better possible risks and how to deal with hazardous substances.

Only when the EU looks at how housing policies can support social and environmental goals will the EAHP deliver lasting impact. Join us and submit your view to the public consultation on the EAHP to shape the future of housing in the European Union starting from what is already here.

By

By  By

By  By

By