New EU carbon border tax to make biggest polluters pay – but not fast enough

The EU’s new Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM), now entering its trial phase, is a step towards global industry decarbonisation. But until it is fully rolled out with a wider scope to mitigate the most carbon-intensive emissions faster, the environment will pay the real price for polluting products.

What is CBAM?

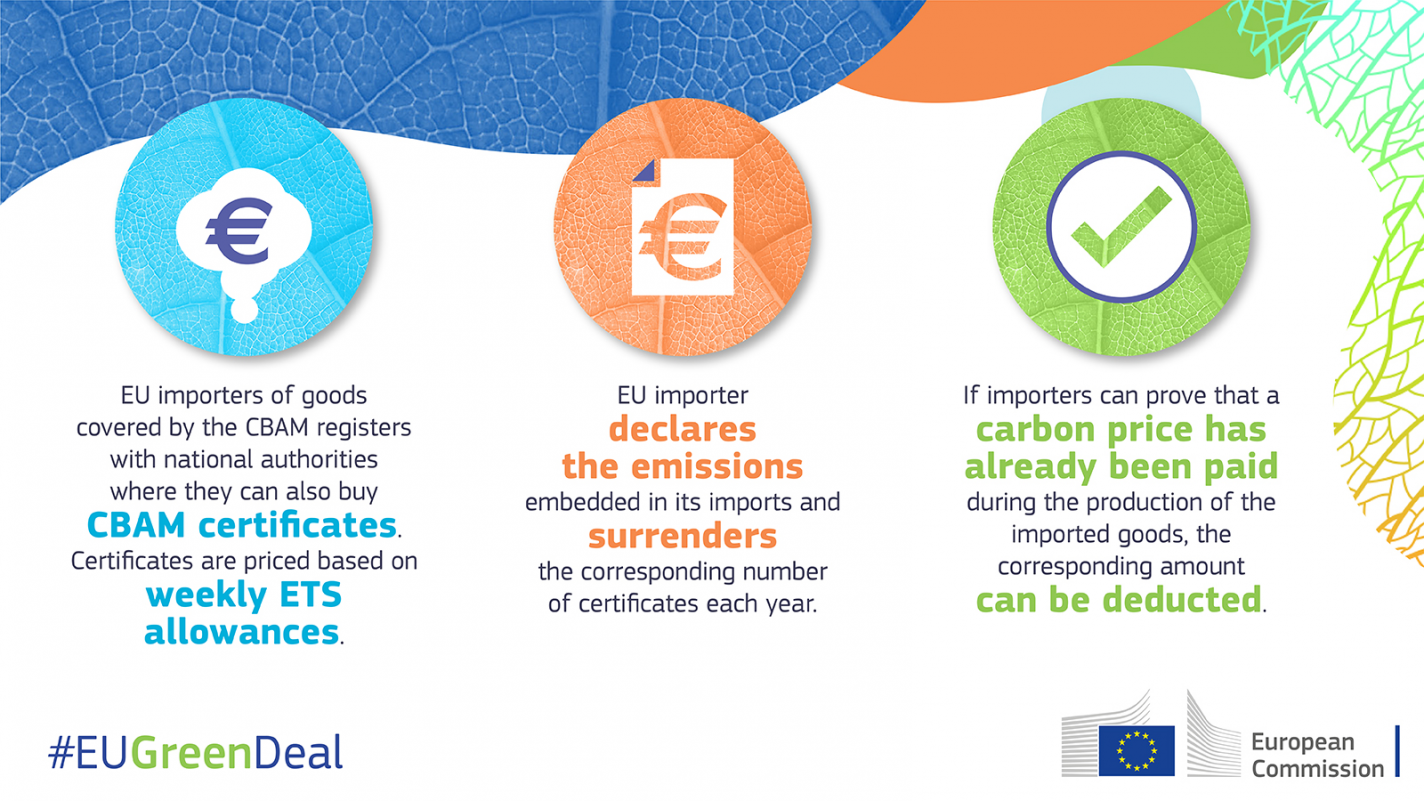

The goal of the EU Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM) is to reduce global emissions by preventing European industry from relocating their production to countries with weaker environmental policies, thus avoiding paying for their emissions. The new rules require importers of industrial goods to buy carbon certificates matching the price they would have paid had the goods been produced under EU carbon pricing rules.

Starting on 1 October, the CBAM has entered its transitional phase, kicking off a gradual process that aims to make the biggest polluters pay – whether their emissions originate in Europe, or not. Cement, iron, steel, aluminium, fertilisers, electricity generation, and hydrogen are all included. Emissions will be determined at a product level, which is an improvement on the CBAM’s counterpart, the Emissions Trading System (ETS), which focuses (less effectively) on production installations.

Following this trial period, the permanent CBAM will enter into force on 1 January 2026 – encouraging the decarbonisation of industry both inside and outside of Europe.

EU revokes free pollution pass for industry

Until now, European companies have not been incentivised by EU law to step away from their non-EU carbon-intensive production processes. Under the new rules, the existing free CO2 allowance for certain industries will be progressively removed. Industry will eventually have to pay the full price for their emissions.

The European Commission also expects that non-EU industry will be incentivised to change their production processes by triggering other regions to put a price on CO2 emissions. Exporters to the EU of cement, iron, steel, aluminium, fertilisers, electricity, and hydrogen may deduct from their CBAM tax the cost of any equivalent payment they have made for emissions in the country of production.

When it comes to the CBAM’s attention to individual products, there is also good news to report. The fact that hydrogen even made it into the transitional phase is of great importance, given the substantial volumes of hydrogen the EU aims to import. For steel and aluminium, scrap content must now be reported on – and a distinction made between pre- and post-consumer scrap. This will promote circularity in steel and aluminium production processes because post-consumer scrap is the only real scrap – anything lost in the pre-consumer phase is an example of inefficient production.

As well as this, only the real source of electricity used in a production process can be included in the calculations of the embedded carbon of imported goods. This prevents companies from using Guarantees of Origin – which do not connect to the physical flow of electricity in the grid, only an unconnected register – to artificially lower the carbon footprint of the electricity they consume.

The environment pays the price for actions that are too limited and too slow

While there are some positive aspects of the CBAM, the rate at which it will be introduced, and the free CO2 allowances phased out, is much too slow. Actions to mitigate catastrophic climate effects resulting from emissions are needed now, not later.

The CBAM also did not rectify some of the known shortcomings of the Emissions Trading System. Under the ETS, producers of steel, hydrogen, and aluminium receive compensation for their indirect emissions (for example, emissions related to the consumption of electricity). Unfortunately, indirect emissions from these products are not included in the CBAM’s scope either.

Putting a cost on emitting carbon matters. The existence of free allowances removed the incentive for industries to decarbonise. Companies will only reduce their CO2 emissions if they must pay for it. Only an ambitious CBAM will achieve this – and until it does, the environment will pay the price.

By

By